October 31, 2013

When I discovered the index card for Compromise Cake, brown with age and handwritten, my first thought was whether my mother ever baked it. And if so, did she ever eat a piece? The woman I knew was an uncompromising character. This cake was not part of her limited cake-baking repertoire by the time I came along, baby number four. In the years following my parents’ divorce, she gave up most efforts to get along with anybody, abandoning the relationships she’d once enjoyed with neighbors, childhood friends, her family, and even her children.

Or maybe they abandoned her, these old friends and casual acquaintances, too fixed on judging this mentally ill and divorced woman, as if mental illness or divorce, like cancer, was something simply not discussed or gotten too close to, lest it prove infectious.

And I suspect my mother’s anger and sadness at how things turned out didn’t encourage others to consider her in a kinder light, something that might have helped her to be less angry and sad when finding herself the divorced mother of four and labeled a mental patient. The only “formal” diagnosis I ever knew of was “burned out schizophrenic,” overheard by my sister, from an unknown member of the medical fi eld. No one told any of us directly what was wrong; all we knew was that one day she was simply referred to as crazy, and nothing could be done about it.

My school friends thought she was just depressed. By the time I reached junior high, she was considered a kind and cool mom, someone who would take in the stray children seeking shelter from harsher, less benevolent parents. She wasn’t one of those adults who provided alcohol for the kids in their home because they thought it a safer way to deal with teenage drinking, but when we smoked dope or did hallucinogens, it’s as if we became tuned into her channel. She always encouraged my art efforts, not even questioning my need to draw directly on the television screen with crayons and markers during the occasional all-night-acid-trip teenage slumber party.

I was too young to know who dumped whom first, my mother or the world. But eventually, the socially gregarious young bride became a sometimes volatile and indifferent woman, and uncompromising in most things, including her cakes.

Most often she baked Devil’s Food cake with chocolate buttercream frosting. It lurked on the sideboard and stiffened with age. My teenage sister’s diet of hamburgers and water left no room for what cake might do to her figure. My brother didn’t trust the ingredients our crazy mother used in her from-scratch creations, eating only store-bought baked goods. I spent the most time at home with her, trying to understand her unhappiness and tempted, always, by the cake on the sideboard. I did my best not to eat it because my siblings assured me that I was fat, their nicknames for me being Chubby, Chubbo, Pudge-o, and Thunder Thighs. Photographic evidence from the period, specifically me posed in fishnet stockings and a skimpy dance costume, show that I was no more than ten or fifteen pounds over the ideal weight, hardly warranting such harassment. Compared to the other chubbos in my dance class, I was positively svelte.

When I found the recipe card for Compromise Cake I thought of how benign the word was in mid–twentieth century America and how troubled a word it is in today’s polarized world. There are those who believe compromise is the nature of life and an organizing principle of civilization, while others refuse to use the word, let alone participate in one.

Our president has been relentless in his efforts to gain compromise with his political opponents. I sent him the recipe for Compromise Cake in a letter sympathizing with his plight. I suggested that he serve it at the upcoming Super Committee on Deficit Reduction meeting, organized in an effort to heal the country’s widening partisan abyss, one side maintaining a policy against use of the “C” word. “You might even wait until they’ve enjoyed a piece or two before you tell them what it’s called,” I suggested. “Then see if anyone chokes!” I did not receive a response and the committee failed to meet its goals.

I rest my case.

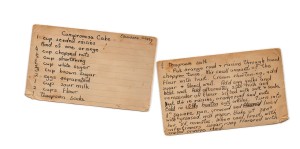

According to the name neatly printed in the upper right hand corner of the card, Eleanore Levey is its author. I don’t know whether she was from the social circle of my mother’s hometown, Burlingame, or one of the Tulelake ladies who doted on her during the year she taught in a one-room schoolhouse, or if she was a former neighbor in our hometown of Castro Valley. But if she was typical for her day, I suspect she didn’t have anything but the best intentions when she wrote the word compromise in front of the word cake.