November 7, 2013

The sugar cookies are round, plump, and pale as a winter moon, sugar grains glistening on their surfaces like snow. Made with butter, all-purpose Gold Medal white fl our, and white sugar the C&H package boasts to be pure cane, they are my family’s communion wafers, the hardtack fueling our march westward.

The sugar cookies are round, plump, and pale as a winter moon, sugar grains glistening on their surfaces like snow. Made with butter, all-purpose Gold Medal white fl our, and white sugar the C&H package boasts to be pure cane, they are my family’s communion wafers, the hardtack fueling our march westward.

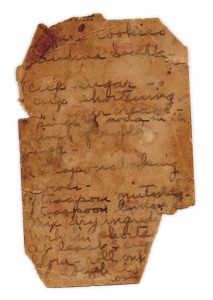

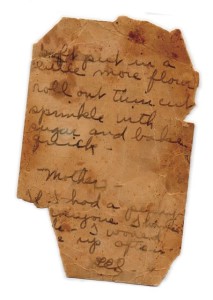

This ancestral recipe, spanning four generations and three centuries on my mother’s side, dates back to 1890 and my maternal great grandmother Caroline Soult, née Hauser, then a Kansas farmwife with a six-year-old son, Harold, my grandfather, and a sixteenyear-old daughter, Maude. Caroline passed this recipe on to her daughter- in-law, Lee Emma Soult, née Stephenson, who passed it on to her daughter and my mother, Marguerite, in the form of a now crumbling card signed LES.

Lee Emma was the sort of ebullient, energetic woman who would not have hesitated to bake a batch of cookies for her grandchildren. Though she died the year before I was born and never made these cookies for me, I still sense her in the kitchen, rolling out the dough. The recipe card is one of the few samples of her writing that I have in my possession, though according to my uncle, she had ambitions to be a writer and a thwarted desire for a higher education. It was her two brothers who graduated from Stanford with engineering degrees after the family moved from Ohio to Northern California when she was thirteen. My grandfather was a fellow student brought home by her brothers to Los Altos for Thanksgiving one year.

As a child visiting my widowed grandfather in his Santa Ana bungalow, I best knew Lee Emma from the sizable collection of cut crystal vases and bowls she left behind. With adult supervision I was allowed to hold these crystal pieces and turn them in the sunlight filtering through the dining room window. Beams of light shot in odd and surprising directions, spattering a wall or mahogany table or dark wooden cabinet surface with bright white spots edged in intensely hued, burning rainbows of light. I wonder now, knowing of her writing aspirations, if this is how the literary urge, failing to find its way to the page, illuminated my grandmother’s life, with blinding moments of awareness edged in a profoundly colored desire for expression.

While Caroline and Lee Emma remain mysteries, I do know their sugar cookies—possibly too well. They brightened my mother’s moribund post-divorce days when our suburban enclave became a kind of prairie, a vast fl at and featureless expanse filled with television and housework and countless empty hours. My mother would make these cookies and our lives would momentarily regain their purposeful pearly sheen before settling back into a sugar-induced slump.

Today the cookies are my madeleine. Like “the whole of Combray and its surroundings, taking shape and solidity, sprang into being, town and garden alike” for Proust when he nibbled his shell-shaped butter cakes dipped in lime flower tisane, these sugar cookies transport me to the garden and kitchen of my childhood. This batch in particular brings me closest to the memories of that time and place.

The most provocative are the slightly underdone, thicker, palest of the offerings, snatched from the oven just moments before they begin to brown. I bite into these and a familiar picture unspools of the generous yard surrounding my childhood home, our patio outside the TV room, the porch swing, the pear tree planted like a jewel set in the midst of a brick-lined circle in a cement-laid pad, what was to be a staging ground for future happiness that never happened, and I’m pulled back into the house from this sunlit, outdoor paradise, into the wan yellow kitchen with its pullout cutting board where my aproned mother works.

To join her I must fi rst pass through the dining room, past the cabinet filled with the hopes that had come with her marriage, the aspirations of class and culture and social standing that never fi t into the flattened postwar suburban landscape.

Displayed behind these glass cabinet doors were stemmed crystal ware etched in an effusive pattern of ribbons, birds, and blooms. Hidden behind the solid wood doors of the lower cabinet was the good china, a delicate fl oral design with subtle touches of gold, and a full set of sterling silver in a wooden chest. Now virtually unused, these accoutrements of our family’s hopes were cast aside, like us, the unwanted encumbrances strewn along the pioneer trail, tossed from the wagon to keep from slowing the others down.

I joined my mother in the kitchen to learn as much as I could about baking. In those post-divorce days, I also hoped that my presence might cheer her up, and her cheer would provide ballast for my own emotional tide. I couldn’t be happy unless she was and it seemed like she was most happy, if she was happy at all, when baking.

Sugar cookies were among her favorites. Despite the firm set of her mouth in the midst of the effort, I imagine her satisfaction in taking a round ball of dough and rolling it out until it was spread as thin as possible across the wooden, waiting for the multiple diminishing cuts of the round, sharp-edged cookie die she so deftly wielded. These cookies conformed to a modern ideal of control, a consistency and replication into an infinite future, the embodiment, I imagine, of her Methodist family’s most essential hopes. Batch by batch, these cookies made up for what she otherwise found so challenging to provide.

The sugar cookies have an irresistible, velvet sweetness, with a lingering aftertaste that always begs for just one more. Lemon zest added to the dough can lend a faint but pointed citrus note beneath the sweet, a reminder not to fall asleep from too many. It was all too easy to succumb to their cloying charms, like the poppy fields of Oz, eating a second and third cookie in hopes of a fleeting cookie happiness, only to wake later, wiping away cookie crumbs and wondering what had happened.

It’s often assumed that sugary home-baked foods are “baked with love.” But in our home, sugar was our sole expression of affection. The pile of sweets mother left on the sideboard as she headed toward her room was the most she was willing or able to say. Television ads of the 1960s encouraged this emotionally entangled indulgence. C&H Sugar’s saccharine commercials featured a lilting, plucking-at-the-heartstrings song played over visuals of doting adults giving cookies, cakes, and lengths of cane to native children whose brown faces ignited in beatific white smiles. When she baked in our kitchen, I became one of those children and my mother one of those adults. This was our pure cane sugar love.

I saw you today on Hallmark. Your mother could have been mine; a bright, energetic woman, whose life plan was interupted by a man (my father) and four children in five years. Though my parents did not divorce right a way, our home was a battle ground between two grossly ill-suited people. My mother became bitter and gave up on parenting and we kids raised ourselves. I well understood your description of the culture during your youth; we were in almost the same time frame. (1950’s)

Walter Boatner (born and raised in Oklahoma)

Walter Boatner

Thank you for your comment, Walter. I am sorry to hear our histories are similar. I am finding out from far too many others about the unhappy compromises between spouses, parents and children, not only in the past, but also in the present. One of the lessons I learned in writing the book is the difference between a good compromise and a bad one. The bad ones lessen and diminish us, are often entered into out of fear and insecurity, which was the case for so many women who felt they had no alternative other than to marry and have children. Good compromises, such as those in a good marriage, are mutually beneficial and agreed upon. I wish you only good compromises from here on out!