February 9, 2018

The Broad blockbuster Yayoi Kusama: Infinity Mirrors closed January 1st. Did anyone notice? No one I knew who wanted a ticket, could get one. The 50,000 first offered online for sale were gone within minutes. A second release of tickets was another big if, an elaborate technical dance pitched to those willing to clamor online, possibly for hours, in a virtual “waiting room.” Determined to avoid that mosh pit, I dusted off my press credentials and snagged an invitation to the media preview.

The Broad blockbuster Yayoi Kusama: Infinity Mirrors closed January 1st. Did anyone notice? No one I knew who wanted a ticket, could get one. The 50,000 first offered online for sale were gone within minutes. A second release of tickets was another big if, an elaborate technical dance pitched to those willing to clamor online, possibly for hours, in a virtual “waiting room.” Determined to avoid that mosh pit, I dusted off my press credentials and snagged an invitation to the media preview.

That was mid-October. Fun while it lasted, by mid-November, I could barely remember the experience. It helped that the show didn’t seem to take Los Angeles by storm, as it did Washington, D.C., or Seattle, where people camped overnight for tickets in the exhibition’s final days. I had proof that I’d been there, a selfie taken in Phalli’s Field, the re-creation of Kusama’s first mirrored room, its floor filled with stuffed white phalli (phallic shapes covered in polka dots.) I got a lotta likes, Facebook Friends called it “cute.” And it was. The ends justified the means.

What has stuck with me regarding Kusama’s work was my first encounter decades ago with one of her ground breaking Infinity Net paintings. The canvas was hanging at LACMA, part of their permanent collection. Done in the early 1960s, it was a minimalist’s obsessive, repetitive, circular single color line of oil paint against a different, solid color background. It was women’s work, like knitting, a painted meditation. According to the wall text, this was part of Kusama’s effort to deal with her own mental illness. As a young woman, she’d come from Japan to great success in New York in the 1960s, then returned to Tokyo in the early 1970s, where she has been living and working ever since in a mental hospital.

Since women and mental illness are amongst my obsessions, the idea of a woman in ‘60s New York trying not to lose her mind, holding onto it by painting these marks as if they were a slender, endlessly looping thread or prayer beads, grabbed me. It was instructional. This is how it is done. This is what it takes. It was sad but hopeful and beautiful, art as anti-depressant for the artist and inspiration for the viewer. I’ve remembered that painting many times since, times I’ve even felt compelled to fill a surface with similar painted marks. Mentioning this seems precious and pitiful, but it wasn’t, it was always a grounding exercise in which I used my attraction to women’s work, recalling the needle arts I’d learned from my mother, while making marks for the sake of making marks, the way men have always been permitted to do.

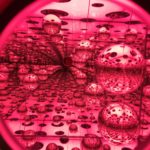

I didn’t follow Kusama’s career beyond that, was ignorant of her other work and how active she continued to be once back in Japan. It wasn’t until the Broad first opened and I was standing in the eternally long line with the rest of the mob for the Infinity Mirrored Room—The Souls of Millions of Light Years Away, a permanent installation, that it dawned on me the painter and the mirrored room maker were one and the same.

The Infinity Room experience is amusing, but transitory, ephemeral, at least the way the public experiences it, 30 seconds at a pop, just enough time for that de riguer selfie. It’s one of those big draw experiences that sucks in museum crowds these days, like LACMA’s Rain Room. They don’t grab from the inside out, not like that Infinity Net painting did for me. The mirrored environments are for the most part just that: mirrors. The point, according to Kusama, is self-obliteration. Selfies are a form of self-obliteration, especially with so many people who take them are trying to look like someone they’re not.

The great gift of The Broad’s Kusama show, as well as the tragedy, since you needed a ticket to access those, was her paintings, not just the later ones that look inspired by PeeWee’s Playhouse, but the somber, earliest efforts on paper. These dark, repetitive, monochromatic patterns of ink and gouache could be an aerial view of the burned out aftermath of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, a horror her homeland experienced when she was just 16 years old and living in a town only 400 miles away. Critics have noted that not enough is made of her mental illness, referred to as a depersonalition disorder, the feeling that one is outside of themselves, which is attributed in the Kusama literature to physical abuse from her mother. Christopher Knight, in his Los Angeles Times’ review, connected her mental health to this mass obliteration. No one else, as far as I’ve read, including the Broad’s exhibit literature, does so. Which is odd, since so much is made of her focus on self-obliteration, press materials calling it her “philosophy.” Without making this dark personal connection to her “Anatomic Explosions,” Nude Body Festivals she staged as anti-Viet Nam war protests, alternatives to atomic explosions in ‘60s New York, the performance is just fun word play, an avant-garde goof on the times. But considering this tragedy as background, it becomes both desperate and brave, a childlike plea for peace. In 1968, she wrote a letter to President Richard Nixon suggesting anatomic explosions instead of atomic ones to end world violence.

The great gift of The Broad’s Kusama show, as well as the tragedy, since you needed a ticket to access those, was her paintings, not just the later ones that look inspired by PeeWee’s Playhouse, but the somber, earliest efforts on paper. These dark, repetitive, monochromatic patterns of ink and gouache could be an aerial view of the burned out aftermath of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, a horror her homeland experienced when she was just 16 years old and living in a town only 400 miles away. Critics have noted that not enough is made of her mental illness, referred to as a depersonalition disorder, the feeling that one is outside of themselves, which is attributed in the Kusama literature to physical abuse from her mother. Christopher Knight, in his Los Angeles Times’ review, connected her mental health to this mass obliteration. No one else, as far as I’ve read, including the Broad’s exhibit literature, does so. Which is odd, since so much is made of her focus on self-obliteration, press materials calling it her “philosophy.” Without making this dark personal connection to her “Anatomic Explosions,” Nude Body Festivals she staged as anti-Viet Nam war protests, alternatives to atomic explosions in ‘60s New York, the performance is just fun word play, an avant-garde goof on the times. But considering this tragedy as background, it becomes both desperate and brave, a childlike plea for peace. In 1968, she wrote a letter to President Richard Nixon suggesting anatomic explosions instead of atomic ones to end world violence.

If you weren’t, like Yayoi, sentient and from Japan in 1945, self-obliteration was groovy in Western youth culture of the ‘60s and ‘70s. If your country hadn’t suffered an atomic attack, you pursued self-obliteration with drugs and rock ‘n roll. Now our selves are being obliterated on every front, like standing in one of Yayoi’s infinity rooms all the time. Where does reality exist and our beings begin? Maybe those million billion selfies we’ve taken since the dawn of digital photography represent our collective angst in the face of growing dehumanization, rather than a record of infinite fun moments.

According to press materials, Infinity Mirrored Room—The Souls of Millions of Light Years Away, the Broad’s permanent Kusama installation “is one of the museum’s most popular artworks…” Maybe that’s not because it is a great work of art but because it’s work, you have to stand in line forever to get in, and then you’re there just long enough to take a selfie. It’s the perfect combination of tedium punctuated by a thrilling burst of self-absorption. Rinse, repeat. And in that, it’s a mirror of modern life.

For some, Kusama represents the democratization of culture. We all become part of her mirrored work, finalizing the connection when we take that selfie. And the selfie culture has become the selfie economy, with special spaces, like the Museum of Ice Cream, built with the selfie business in mind. Kusama has been called the It Girl of the Selfie Economy.

At age 88 (89 this March), Kusama remains incredibly productive, cranking out paintings and sculptures and mirrored rooms as well as recently opening her own museum in Japan. Apparently she can’t or doesn’t sleep much. An all-nighter for her, back in the ‘60s, might produce the 33 foot long Infinity Net painting in the Broad’s show. They displayed the foot high piece that was trimmed from the bottom of a floor to ceiling work to make it fit on a New York gallery wall. My only question was what does she eat for all that energy? The Broad’s marketing person said, sadly, she had “no clue.”

Kusama dresses in an orange wig, wears loose fitting outfits made of wild patterns taken from her work. Time Magazine named her one of the most influential people in the world. She is like a clown prophet. What are we to make of her insistence on self-obliteration, which she defines as “to revolve in the infinity of endless time and the absoluteness of space, and be reduced to nothingness.”? Is it for everyone? Or is it, as some Buddhists believe, our only hope?

Kusama dresses in an orange wig, wears loose fitting outfits made of wild patterns taken from her work. Time Magazine named her one of the most influential people in the world. She is like a clown prophet. What are we to make of her insistence on self-obliteration, which she defines as “to revolve in the infinity of endless time and the absoluteness of space, and be reduced to nothingness.”? Is it for everyone? Or is it, as some Buddhists believe, our only hope?

For those interested in further contemplating such questions while scrambling for tickets, the show is soon to open (early March) at the Art Gallery of Ontario and will be at the Cleveland Museum of Art from July thru September. Or, you could look into The Broad’s next blockbuster Jasper Johns: Something Resembling Truth, scheduled to open tomorrow. With Johns less easy to like than Kusama, and truth currently less available than obliteration, the tickets are an easier catch. As of this writing, only 11 days are sold out of the three-month run.

Bravo!!!! Every word. Bravo. At some point we have to meet for coffee.