January 25, 2026

Hello, how are you and thanks for asking–I’m busy prepping for another iteration of Creative Cafe: Food & Writing for UCLA Extension’s Writers’ Program. I’m especially excited as it’s being held two half-days, February 5 & 6, in the Extension’s new downtown L.A. building at 433 S. Spring Street. Even more exciting than gathering in person for the first time since Covid, will be our first ever field trip to the nearby Grand Central Market for lunch and tons of food writing inspiration. So, while I get ready for that, you just go on and enjoy this particularly appropriate rerun from 2017. It contemplates the direction the restaurant world was taking back in someone’s first administration. Unfortunately, it’s ripe for another slice of contemplation. Thus I give you What’s Eating Us, Part 1 (Redux),from May, 2017.

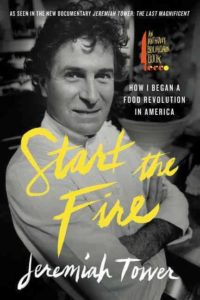

What is eating us? By that I mean what is going on with food in restaurants, markets, homes, our mouths, these days? Why has fine restaurant dining become such a brutal experience? When did it become all about the photograph of what you’re eating rather than the food? When did all manner of food restrictions, both real and imagined, become the norm and the formula get flipped from living to eat to eating to live? Those are just some of the questions I’ve been muddling over for a while now, with the best of intentions to write on, but am finally writing up after enjoying the new documentary Jeremiah Tower: The Last Magnificent and reading his reissued 2015 memoir, California Dish, now titled Start the Fire: How I Began a Food Revolution in America.

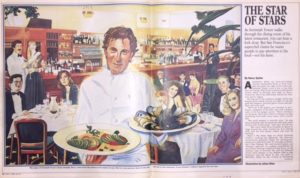

I profiled Tower, one of America’s first celebrity chefs, in 1984, for West Magazine, shortly after he opened the late, great Stars in San Francisco.The article titled “The Star of Stars,” opened with him tenderly turning rust-and-cream-colored chanterelles for that night’s marrow-and-chervil cream sauce in brioche, then, when sufficiently tanned the next day, their own savory ragout. He was cool, collected and the real epicurean deal. Plus he had sex appeal. “The Ronald Colman voice,” I wrote, “the ‘sad Escoffier eyes,’ classic WASP profile and a chin strong enough to wear a pork chop panty have earned him a name as the Cary Grant of the cuisine scene.” Everybody wanted some of his sizzle.

The Harvard architectural school graduate without any formal culinary training started his cooking career at Chez Panisse in the ’70s. Answering a chef wanted newspaper ad placed by a desperate Alice Waters, he was hired on the spot when he saved the night’s soup (a little salt, a little cream). He left after years as a partner to Waters, to revamp San Francisco’s Balboa Cafe and Berkeley’s Santa Fe Bar and Grill. He soon made his own mark with Stars, one of the great restaurant scenes of San Francisco in the ’80s, only to then disappear, both the restaurant and the man, in the ’90s. Earthquakes, both literal, personal and professional, were to blame. Now he’s making a comeback with the aforementioned movie and memoir while living between New York, where he does restaurant consultation, and Mexico, where he flips houses and scuba dives.

Reading Start the Fire, I am now up to the ’90s and his bitter parting with the San Francisco’s delicious decadence, I haven’t answered my questions but I have been reminded of what I once found so deeply engaging about the food scene, what I fear the culture has lost in the intervening decades. Tower in his youth and young adulthood was after the experience of food, reveling in it, savoring it, seeking out the sublime. It was a way for him to consume the world, to experience life, but it was also about quality, not quantity.

Tower’s gastronomic training came from a childhood spent traveling the world, being left alone in grand restaurants and dining rooms, on luxury liners and in deluxe hotels, where his favorite literature became menus, menus that told him stories of the meal, the people and the places partaken of. A teenage Tower learned to save the day when his drunken hostess mother passed out before dinner was served. At Harvard, he ate, drank, cooked and made merry with all the other bright young things crowding that Ivy League campus.

He brought Old World elegance and style to the hippies-cooking-for-their-friends ethos at Berkeley’s Chez Panisse in the 70s. But for the most part he lived in San Francisco. When I read that, I realized why his life stint at Chez Panisse wasn’t meant to be forever. I lived in San Francisco in the ’70s, as well, and San Franciscans back then made fun of Berkeley’s Birkenstock and plaid flannel shirt ways. With Stars, Tower created something never experienced before in Northern California. Taking inspiration from French bistros such as Paris’ beloved La Coupole, he created a place where people from all walks enjoyed setting foot, whether San Francisco’s social aristocracy, major media characters, politicians or just hungry-for-sophisticated-fun folks. Everything was aimed at the diners’ pleasure, from the posh and lively menu to the elegant decor to the jazz pianist. My memory is of a place where all who entered felt celebrated.

Now, compare that to today’s “hot” restaurant experience. The noise level is so high, you cant hear a word of conversation and leave with a sore throat for trying to be heard. Or the dining room is uncomfortable by design for faster table turnover. Or, there are NO tables, like the award winning latest best Venice thing where you ate the expensive little plates of exquisite victuals on tables and chairs you made in the parking lot from stacked milk crates. Seriously. As for the food, the more absurdly complex and mysterious a dish, supposedly the better. Like molecular-gastronomy, which was fun for about a minute, but really, smoke and foam can only go so far. And if you can’t do complex/mysterious, go for big, as in the hottest chilies or the loudest bacon, bacon being the culinary equivalent of “Look, a squirrel!” Tower sought out the best ingredients, cooked them with a deft and subtle touch and grilled a lot. He kind of got the mesquite wood grilling thing going. Now everyone has their wood fired ovens, and those are great fun, but boy, reading his book, makes me want to start a bring back mesquite movement.

Hey, I know a lot of you might say these are first world problems. You might say that there are other things we need to deal with immediately, if not sooner, like our dangerous “Look, a squirrel!” president. A man who doesn’t drink and therefore will never know the apparently exquisite pleasures of a Chateau d’ Yquem enjoyed with roast beef. Well, neither will I, but that’s because 1) I can’t afford the esteemed Sauterne and 2) I haven’t eaten beef since the aughts, but that’s another story. My point is that our current POTUS is a gold plated vulgarian. To the extent he reflects the loud, crass, vulgar, dangerous culture that we’ve become, I would say, that’s a problem. For all of us.

What I will also say, before I head off to try Tower’s Grilled Garlic and Ancho Chili Sauce (p. 178) for the fish that I do eat, that we could all benefit by tuning in and turning our senses back on to the subtleties of truly great food. That begins with incredible ingredients waiting in vast array at Farmers’ Markets, returning to our kitchens, even if only occasionally, and reminding ourselves of the exciting creative adventures to be had there, and going to restaurants that not only make exciting food but make us feel exciting and heard and seen and appreciated while we are there. Hey, I’ve got a list, “e” me and I’ll share it. And no, the table is no place for a cell phone or an iPad or a laptop when in the company of others. These few simple steps can start us back in the direction of the humanity and civility of yore, or even the ’70s, where that food revolution began, at the table and in the kitchen and in our mouths.