April 15, 2021

In advance of my upcoming Writers’ Banquet (food and memory) workshop for UCLA Extension Writers’ Program (see classes above) I’m happy to share this excerpt from Compromise Cake: Lessons Learned From My Mother’s Recipe Box. Now, put yourself back in front of a Zenith TV, circa 1960 something, forget about that pandemic and enjoy!

As women gained greater independence from the kitchen, working outside the home and building careers instead of baking cookies, American industry stepped in with tempting, easy to make eats. My mother’s community of cooks never had a chance. Their charming but dutiful, if not downright dull offerings, exotic in name only, helped prime the public for the postwar onslaught of advertisers hawking their alluring wares. Having survived the Great Depression and war time rationing, home cooks were ready to abandon their prune cakes parading as Prussian and nut-less nut bars for exciting processed conveniences from Kraft Foods, Pillsbury, General Foods, General Mills and Nabisco. Ours was the greatest country to ever walk the earth and our reward was Campbell’s Soup, Sugar Frosted Flakes, Cheez Whiz and Minute Rice. Kraft’s party planning television ads were the most tempting to me. Avuncular announcer Ed Herlihy was the hostess’s Pied Piper, his warm velvet voice like a vat of melted Kraft Caramels. Whether a holiday-buffet, football bowl celebration or teenage dance fest, Kraft’s tribe was always cooking up a dazzling spread. Worries about atomic war, riots and political assassinations were kept at bay with copious amounts of Kraft American Singles, Miracle Whip, Miniature Marshmallows and caramel dipped apples. Our greatest fear in Kraft’s America of the 1960s was a sudden shortage of fat and sugar. Anything could be survived as long as Kraft’s fount kept flowing.

As women gained greater independence from the kitchen, working outside the home and building careers instead of baking cookies, American industry stepped in with tempting, easy to make eats. My mother’s community of cooks never had a chance. Their charming but dutiful, if not downright dull offerings, exotic in name only, helped prime the public for the postwar onslaught of advertisers hawking their alluring wares. Having survived the Great Depression and war time rationing, home cooks were ready to abandon their prune cakes parading as Prussian and nut-less nut bars for exciting processed conveniences from Kraft Foods, Pillsbury, General Foods, General Mills and Nabisco. Ours was the greatest country to ever walk the earth and our reward was Campbell’s Soup, Sugar Frosted Flakes, Cheez Whiz and Minute Rice. Kraft’s party planning television ads were the most tempting to me. Avuncular announcer Ed Herlihy was the hostess’s Pied Piper, his warm velvet voice like a vat of melted Kraft Caramels. Whether a holiday-buffet, football bowl celebration or teenage dance fest, Kraft’s tribe was always cooking up a dazzling spread. Worries about atomic war, riots and political assassinations were kept at bay with copious amounts of Kraft American Singles, Miracle Whip, Miniature Marshmallows and caramel dipped apples. Our greatest fear in Kraft’s America of the 1960s was a sudden shortage of fat and sugar. Anything could be survived as long as Kraft’s fount kept flowing.

While I salivated at the ads, neither my mother or I ever actually made anything they touted. I did harbor a secret longing to live, like so many of my friends did, on Kraft Macaroni and Cheese dinners. I wanted to be like all the other kids instantly making a glowing bowl of macaroni bathed in an other-worldly orange of Kraft’s powdered processed cheese food.

But my inconvenient mother insisted on making her own from scratch version of macaroni and cheese. She’d use actual cubes of cheese cut from a block, Colby or cheddar, Kraft’s Velveeta on occasion, cooked macaroni, butter, translucent onion bits, milk and rubbery slices of broiled bacon that made for a leaky, squishy, separated out and all too real repast. There was an actual brown crust that formed on top of her macaroni and cheese, which was pulled from the oven after a leisure baking time, not whipped up in a trice on a stovetop. Her version took several hours to produce. It was not a dish for the impatient or the squeamish.

My mother remained steadfast in her pre-world war II culinary practice, while we, her hungry, cranky baby-boomed spawn begged her to come with us into the 20th century’s second half. She clipped some recipes from commercial sources, but never made them. Her leap into food’s industrial future cut to the chase, adopting artificial convenience foods NASA designed for outer space journeys or bomb shelter visits, such as Folgers freeze dried instant coffee crystals and Cool Whip, that synthetic, non-dairy dessert topping that comes frozen in tubs. I knew the woman who had once proudly devoted herself to whipping real cream with a hand cranked egg beater was ready for the space station when a container of Cool Whip became a permanent fixture in our refrigerator.

By that time, she was long past the need for such quick fix hors d’oeuvres as “mushroom tempter,” or “lobster delight” or “bacon and peanut butter” treats detailed on Golden State Dairy Products cards, kept on hand for guests who never dropped by.

Among the commercial recipe offerings my mother saved was an insert from a sack of Gold Medal flour featuring “Pat-in-the-Pan Pie Crust.” Perfect for either beginning or burned-out pie makers, it promises a “tender cookie-like pastry that needs no rolling, no special skill.” The easy crust could be filled with “Betty Crocker Ready-to-Serve Pudding.” With tongue possibly in cheek, the copywriter added “There’s a Gold Medal Memory for you!”

By law, a pie, and one’s memories of it, should be more than a can of pudding dumped into a crust that’s been patted into the pan. Any cook as unskilled or exhausted as that should find a nice bakery from which to purchase dessert.

Of my mother’s few recipes representing that era’s commercial food industry, the one I chose to make was Cheesecake Pie with Florida Orange Glaze. It was from another Betty Crocker’s Pie Ideas insert (both having been salvaged from 10-pound sacks of “Gold Medal, the White Thumb Flour”) which encouraged bakers to “swing into spring with a shower of Pie Ideas!”

One reason for choosing the recipe was that its author, Betty Crocker, was a hugely influential, entirely fictional corporate character who had become the second most popular woman in the United States by 1948. Eleanor Roosevelt was then number one. The widowed former first lady was a liberal social activist who urged women to be strong, independent and involved in their communities beyond the kitchen. Betty Crocker encouraged women to believe in a world best served by dessert.

Eleanor Roosevelt, as if feeling pressure to compete with Crocker, the invented industry flogger, officiated at the first Pillsbury Bakeoff, held in 1949, which she endorsed in her syndicated newspaper column as a “healthy, all American project.”

My mother saved only one Pillsbury Bakeoff recipe. But the clipping for Mrs. Helen L. Pentleton, of Mattapoisett, Massachusetts’ “senior second prize winner” praline crunch cake from Pillsbury’s 9th Grand National Recipe Baking Contest, had deteriorated to the point of illegibility. It looked like someone had either folded it too many times in aborted urges to make it, or nibbled it in a reverie while imagining the results. Whatever the truth was regarding Pillsbury’s lack of influence in our house, for as long as I knew her, my mother’s white thumbs belonged to the marketing behemoth Gold Medal.

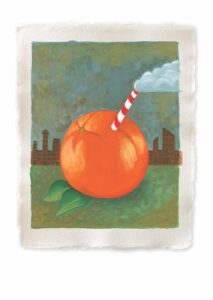

Another reason for choosing to make Crocker’s orange glazed “pie idea” to represent the industrial revolution in America’s post war kitchens were its main ingredients of cream cheese and frozen concentrated orange juice. The orange juice in the recipe was designated as being from Florida, as if there were any other, and as I have found out, there is not.

But first, to the cream cheese, specifically Kraft’s Philadelphia Brand, in its singular silver foil wrap. This turn of the 20th century industrialized American food creation was a staple of our kitchen. Like Kleenex stands for facial tissues, the brand name Philadelphia now stands for cream cheese internationally. In Spain it is queso filadelfia.

Cream cheese is a pure white block of endless possibilities. My mother didn’t need a recipe to put a chunk of it to work. All she did was throw it in with some mayonnaise and room temperature butter and pressed cloves of garlic for an instant party, with her legendary, long lingering garlic cream cheese dip.

I grew up believing cream cheese was essential to human existence, an infinitely compliant cushion against the blues. Countless tangy, ingratiating bricks of it disappeared in our house. We had both the savory and sweet sides covered when my teenage sister learned in home economics class to make a fine New York-style baked cheesecake. Kraft’s Philadelphia Brand Cream Cheese gets much of the credit for my childhood thunder thighs and gently doubling chin.

As for orange juice from Florida, as specified in the recipe, this was the ‘60s and the post war Florida juice industry had crushed the citrus trade. As a native California kid, I was left to wonder what was wrong with our state’s juice? The entirety of Southern California was planted in oranges. My grandfather grew them. I cannot smell an orange blossom without picturing the front yard of his Santa Ana bungalow.

As a child I fretted at the winter news reports about killer frosts threatening the state’s citrus crops. I knew at a tender age that a smudge pot was a device holding a fire in the midst of the groves while a fan blew warm air through the trees to keep the crop at a safe temperature. I pictured the smudge pots glowing red in the middle of the orchards and I worried about the crop and our state’s economy. But what worried me the most was why were we, Californians, forced to drink orange juice from Florida?

Was California juice inferior? Unsafe? Illegal? My father taught me how to peel an orange by cutting off the top and bottom, and scoring the fragrant bright skin into sections that peeled easily away, leaving delicious traces of orange skin and its pungent oil beneath my fingernails and on my hands. We did this outdoors on sunny mornings during our summer vacations at cabins in the Sierras. The sight and smell of pine needles are indelibly mixed for me with this exercise.

Orange juice, on the other hand, was a hard, cold, cardboard cylinder that had to be defrosted and combined with sufficient water to consume, or it was drunk with breakfast at a Formica table-topped diner. Orange juice, frozen and concentrated from Florida was not a sensual experience.

When I thawed a can to make this pie, I was reminded of the sharp, chemical taste of frozen concentrate orange juice that I hadn’t experienced in years. For decades now the only orange juice I’ve drunk has been fresh squeezed with its bright, natural, real flavor. I prefer to eat a whole orange bought from the farmers’ market, which I slice for my morning fruit and enjoy one beautiful, shimmering wedge at a time. Sometimes these oranges are wonderful, occasionally remarkable, with delicate, complex and nuanced tastes. Other times they are disappointingly flat, dry, and maybe even, worst of all, sour, the victims of drought or frost.

This unpredictability in oranges is an intimate reminder of the authentic world. I become concerned for where I buy my oranges, their variety, where they were grown, and that year’s weather. I keep mental notes on which growers and supermarkets care more about quality and which care more about price. A frozen cylinder filled with flavor corrected juice can’t begin to provide this. It’s the difference between a real friend and a frozen, concentrated Facebook one.

An orange peel can be as valuable as the fruit’s juice, adding zest to a stew or with butter and garlic for broiled fish or chicken. Recently I discovered the technique of drying orange zest in a slow oven and grinding it into powder for a pungent note to add to pies, whipped cream or savory dishes. I’ve also enjoyed bouts of making candied orange peel, best done from organically grown fruit, for eating bare or dipping in chocolate. Good luck trying to get any of those from a can!

The condensed juice industry’s post war creation is a textbook illustration of technology’s triumph over nature. When John McPhee profiled the booming Florida juice industry in the New Yorker in 1966, he told how scientists found a way to boil orange juice in a vacuum until “highly viscose,” separate it into multiple parts, flavor and reassemble it for packaging and freezing in small, round cans. As McPhee explained, Florida’s hot, wet climate produced a high water content fruit ideal for juice, while California’s drier climate produced sweet, thick-skinned oranges low in juice and best eaten fresh. He further noted that oranges had once been the most popular fresh fruit in the country. By 1966, consumption of the fresh fruit fell 75 percent. “Fresh oranges have become,” McPhee wrote, “in a way, old-fashioned.”

Today it’s the concentrated juice that seems old fashioned. The frozen juice section in my local chain supermarket has nearly disappeared. Our farmers’ markets and supermarkets are piled high with multiple varieties of the fresh fruit. Vendors stand at our freeway off ramps selling cheap bags of oranges. The concentrated juice is relatively costly. With such affordable fresh options at every turn, at least in Southern California, frozen concentrate seems absurd.

For the most part and on top of that, the commercially processed juice business has been taken over by bottles and cartons of fully constituted juice labeled as “natural” and “not from concentrate.” But these juices are at least pasteurized and at most flavor corrected to a disturbing degree of conformity. And most of the juice known as orange no longer comes from Florida, but is now shipped via tanker from Brazil.

Betty Crocker’s Cheesecake Pie with Florida Orange Glaze also calls for a can of chunked pineapple for the glaze, another once popular mid-century item now off the radar. Pineapple, the legendary tropical fruit, represented luxury and hospitality in Europe beginning in the 1600s. It was a trophy served at royal courts. But for California suburbanites in the 1960s, pineapple meant Hawaii. To me, Hawaii meant orgasmic television game show contestants winning all expense paid vacations. Pick the right door or guess the right price and be greeted on sandy shores by grass-skirted natives bearing pineapples.

Today, I rarely eat pineapple, whether canned or fresh, the former being too sweet, the latter being too acidic and too much trouble to wrestle to the plate. Their association with tired fruit salads and Jell-O has further ruined both options for me. As an adult, I’ve made multiple trips to the Hawaiian Islands, and they were nice, but never as exciting as they seemed to those game show contestants. Mango is now my fresh tropical fruit of choice and numerous other destinations are of greater interest than Hawaii. I now wonder if the natives whose islands have been consumed by the travel industry would rather throw pineapples at tourists than serve them.

This pie is a fine example of American Industrial Eats, a tangy reminder of factory food’s shining mid-century promise. For extra tang, make it as I did, with a graham cracker crust. But don’t tell Betty Crocker, lest she string you up by your other than white thumbs.

cheesecake pie

2 8-ounce packages cream cheese, softened

2 eggs

½ cup white sugar

1 6-ounce can frozen orange juice concentrate, thawed

9-inch baked pie shell

Heat oven to 350°. In large mixer bowl, beat cream cheese. Beat in eggs and sugar until smooth. Mix in ½ cup of the concentrate, reserving remainder for glaze. Pour into baked pie shell. Bake 30 minutes. Spread warm Florida Orange Glaze carefully over hot pie. Chill at least 8 hours.

florida orange glaze

½ cup sugar

¼ cup flour

½ cup water

¼ cup reserved orange juice concentrate

1 can (8-1/2 ounces) crushed pineapple, drained

In saucepan, blend sugar and flour. Combine water and concentrate; stir into sugar mixture. Cook, stirring constantly, over medium heat until mixture thickens and boils. Boil and stir 1 minute. Stir in pineapple.

Note: Original recipe called for Gold Medal flour and Florida Orange Juice concentrate.